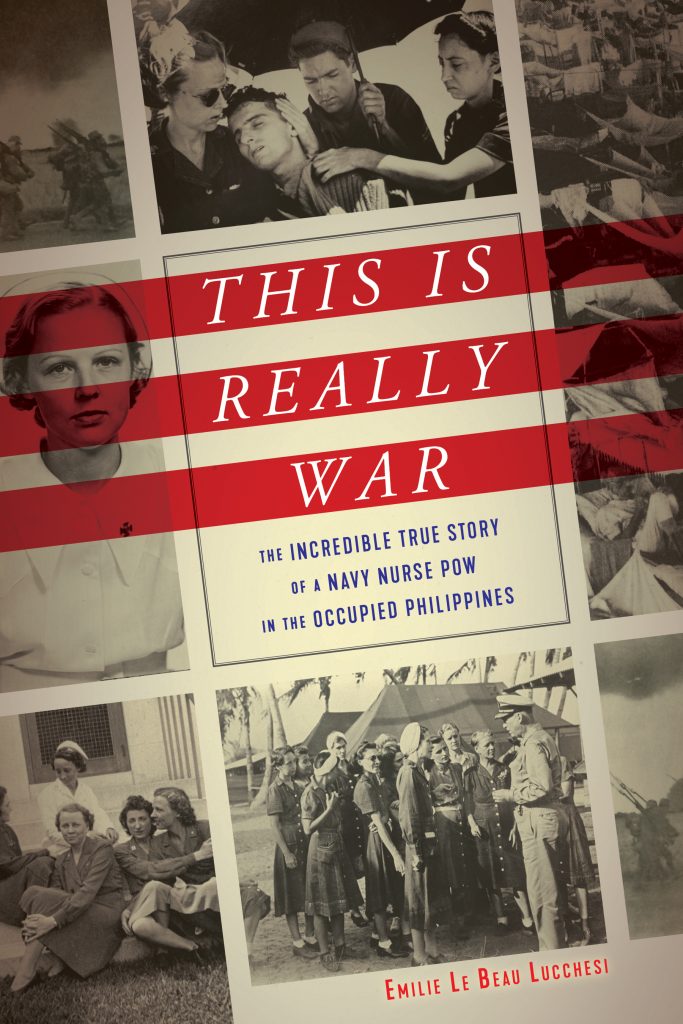

Read below to learn about Emilie Le Beau Lucchesi’s challenges during the research and writing of her newest book This Is Really War and what she hopes readers will take away from the story.

This Is Really War is a groundbreaking history of the US Navy nurses held prisoner in the Philippines during World War II and the dramatic rescue operation to end their captivity. In the book, you follow Dorothy Still’s story, one of the “Twelve Anchors,” the nurses who served in the Santo Tomas and Los Baños prisoner of war camps. What drew you to her as the main character?

I found Dorothy to have an honest quality that was so likable. For example, the liberators lit the barracks on fire during liberation to motivate sluggish inmates to evacuate. Dorothy was on duty at the infirmary and couldn’t return to the barrack to collect her belongings. Her belongings at that point were minimal—we’re talking a sliver of soap, letters and a drawing pad. The camp dentist made sketches in the pad and she treasured them very much. When she lost the pad, she felt so hopeless and lost. She actually sat on the stairs to the infirmary and felt so hopeless. It was such an honest moment to admit, and that made me appreciate and like her.

Another element of her honesty was how she felt she was often the target of her chief nurse’s criticism. At 28, she was the one of the youngest of the group, and she felt her mistakes never went unnoticed. You’ll notice in photographs that she always positions herself far from her chief nurse. I loved that about Dorothy. Haven’t we all had that dreadful boss?

As Memorial Day approaches, how can this book help people to understand and celebrate those who served our country?

This book can help us broaden the lens as to who we celebrate as veterans. Many women have served our country in a great capacity. We should also honor our medical corps. We have few stories from our medical corps and I think we need to broaden our definition of hero.

In Ugly Prey, you write about Sabella Nitti, an innocent woman who was accused of murdering her husband. What was the biggest difference between writing Ugly Prey and This Is Really War?

In my work, I am looking at stories that were not told during their time or were not acknowledged properly. Our historical lens is narrow and I’m seeking an expansion, particularly one that includes women’s stories. So both Ugly Prey and This Is Really War are my efforts to revisit stories that need to be told. For me, Ugly Prey had such a familiarity to it—an Italian American woman in Chicago. This Is Really War took me to a different country and into the medical corps. Fortunately, my contact at the US Navy’s Bureau of Medicine and Surgery gave me an abundance of information and quickly responded to even the tiniest questions.

I also have to note that writing This Is Really War was a greater emotional challenge. I read a tremendous amount of oral histories and historical records from survivors of the civilian and military POW camps. It put me into empathy overload. Most of what I read did not make it into the book, as it was for my own education. But I think I will remember those words for a long time.

I also became increasingly aware of food waste. These inmates were starving by the time of their liberation. So I must admit there was a time when throwing out food in my presence involved me saying, “You know, at the end of the war…”

What do you hope readers will take away from reading This Is Really War?

I want readers to love and respect Dorothy and the other navy nurse POWs. I want them to see these women as heroes who fought for life in a concentration camp. I also want readers to understand that as medical corps, they were subject to great trauma that was never acknowledged or treated.

What five people—living, dead, fictional or nonfictional—would you have over for a dinner party and why?

I’ve thought about this quite a bit. First, I would have my grandfather, Dr. Leon J. Le Beau, PhD. He served in the South Pacific in WWII in the army as medical corps. We spoke only at surface level about his experiences, which was very typical for his generation. Next, I would invite Dorothy Still and Margaret “Peg” Nash, two of the navy nurse POWs. Peg was such a spirited young woman. The title of the book came from her, as well as many of the chapter titles. I really liked her as I researched her, and I think we would be fast friends. Next, I’d like to invite Helen Cirese. She was the young attorney who saved Sabella Nitti’s life. She was also a fellow resident of Oak Park, Illinois, so we went to the same high school, albeit seven decades apart. I’m researching Helen and I’d like to write a book about her. She was a pioneer! Lastly, I’d like to invite my husband’s great-great-uncle “Cuco.” I’m researching him for a book on everyday heroes. When my mother-in-law and her family wanted to immigrate to the US from Cuba, they were deemed “enemies of the state” by Castro’s government. My husband’s abuelo lost his job and they were destitute. Cuco snuck them food each week at his own risk. I’d like to meet this family legend.

The next question is, what would I serve? We talked about this. My grandfather traveled the world and lived in Asia for part of his adulthood. He has a very diverse palate (which regretfully included tofu in the 1990s). I think Dorothy and Peg are also pretty open. Helen Cirese would likely appreciate a nice, home cooked Italian meal, but that might be too foreign for Cuco. This ruled out eggplant parmesan or risotto. In the end, we decided on chicken vesuvio with vesuvio potatoes. It’s a specialty of Chicago! Dessert is flourless chocolate cake because it is my very favorite. And we’d have plenty of wine, of course, so I can toast these five great people.

No Comments

No comments yet.