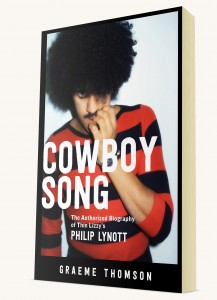

“The Boys Are Back in Town” by Irish band Thin Lizzy is a timeless rock anthem that is instantly recognizable to music fans everywhere, and their classic albums Jailbreak and Live and Dangerous are now part of the rock canon. In Cowboy Song, author Graeme Thomson analyzes lead singer Philip Lynott’s childhood in working-class Dublin, his stardom with Thin Lizzy and his drug-induced decline. It is the first biography of the musician written with the cooperation of the Lynott estate and shares the extraordinary life and career of the supremely talented songwriter.

“The Boys Are Back in Town” by Irish band Thin Lizzy is a timeless rock anthem that is instantly recognizable to music fans everywhere, and their classic albums Jailbreak and Live and Dangerous are now part of the rock canon. In Cowboy Song, author Graeme Thomson analyzes lead singer Philip Lynott’s childhood in working-class Dublin, his stardom with Thin Lizzy and his drug-induced decline. It is the first biography of the musician written with the cooperation of the Lynott estate and shares the extraordinary life and career of the supremely talented songwriter.

In this post, author Graeme Thomson shares his list of his favorite Thin Lizzy songs and explains how they embody the unique blend of cultural influences that inspired Lynott’s writing.

Whenever the archetypal rocker, with his studded wristband, predatory leer and leather trousers, is described as possessing the qualities of a poet, this helps explain why. Lynott’s first great song about the city that formed him is a beautiful, conflicted ache from his tender spot.

From Cowboy Song: It was written as a poem, and there is a charming recording of Lynott reading it as such, but it resonates more strongly when sung to music. It’s an important song, not just for Lynott but for Ireland. “Aside from things like ‘Molly Malone’ and ‘The Auld Triangle’, nobody really said straight up in a lyric: Dublin,” says [Lynott’s childhood friend] Paul Scully. “It was quite a revelation. We heard Dublin mentioned in a song with a strong Dublin accent, as opposed to Ray Davies singing about London. It was ours. Ireland always had an inferiority complex about England, so when Philip sang proudly and poetically about Dublin, that was an amazing moment.”

The B-side of “Whiskey in the Jar” was Lynott’s first concerted attempt to engage with his non-Irish roots. Born in England to a white Irish mother and a black Guyanese father he barely knew, and raised by his grandmother, he specialized in identity quests and mythic creation stories. As so often, beneath the swagger lies acute vulnerability.

From Cowboy Song: The subtext states: I’m here and I’m different, what are you going to do about it? More importantly, what am I going to do about it? The music—dominated by [Eric] Bell’s juddering, ragged-edged guitar riff—conveys the simmering threat of an antagonistic street encounter. Possessed of a lean power and a very clear sense of its own purpose, in little more than three minutes the recording made almost everything the band had released previously seem rather whimsical by comparison.

A big, romantic, hugely satisfying burst of windblown folk-rock, and one of the prime exhibits in Lynott’s stated aim to “write contemporary Irish songs.”

From Cowboy Song: During Thin Lizzy concerts, Lynott would introduce “Wild One as “a song about running away.” It’s an Irish song, alluding to the nation’s long and complex dance with exile [but] it would take a tin ear and a particularly hard heart not to also hear it as a deeply personal song from a son to his free-spirited mother, who had first run away from Ireland and then—as the child in Lynott couldn’t help but perceive it—from him. “Wild one won’t you please come home / You’ve been away too long, will you?”

Simply one of the great Friday night rock ‘n’ roll anthems: dueling guitars, unfettered machismo, blood, beer, street poetry and ragged romance. Ah, the irresistible lure of tall tales and long summer evenings.

From Cowboy Song: What elevates “The Boys Are Back in Town” to art is Lynott’s understanding that the greatest, most enduring legends aren’t created in the doing, but in the retelling. In urging his audience to remember “that time down at Johnny’s place” and “that chick that used to dance a lot,” he not only makes it a communal experience, he embellishes and layers, heightening their exploits to the realm of folklore. It is a song about storytelling as much as it is a song telling a story.

A fond, finger-clicking recollection of teenage misadventure on the streets of south Dublin, and an affectionate homage to Lynott’s long-standing love of Van Morrison’s blue-eyed soul, with a passing nod to Bruce Springsteen and the E Street Band.

From Cowboy Song: It was a timely reminder of Lynott’s most persuasive and enduring gifts. He was a craftsman when it came to mood and melody, and a singer of rare versatility. The way he would bite down on the words, roll them around his mouth, chew on each syllable and stretch it out. It was an art form. It certainly impressed [producer Tony] Visconti. “He was like the Sinatra of the rock world,” he says. “A highly-nuanced voice, and so expressive.” It’s not really a rock voice at all. The wood-smoke timbre, the high-wire sense of timing and off-beat phrasing position Lynott closer to folk and jazz. He was a crooner seduced by high voltage and heavy wattage.

From his second solo album, and the best and brightest song Lynott wrote (with Rainbow bassist Jimmy Bain) in his later years. With its classic chord changes, baroque piccolo solo—consciously mimicking the Beatles’ “Penny Lane”—and a lovely midnight-blue breakdown, “Old Town” might be Lynott’s finest pop moment.

From Cowboy Song: It’s a break-up song, but it’s also a Dublin song. The seed of the idea dated back to a session in Windmill Lane Studios in 1981, when Lynott was recording a version of “Dirty Old Town.” David Heffernan’s panoramic video transformed it into something like an elegy for Lynott’s home city, trailing him as he strolled around Grafton Street, the Ha’penny Bridge, the Liffey and Herbert Park. At the end, as he pulled up his collar and wandered along Howth harbour towards the lighthouse, it felt like a story that had begun with “Dublin” thirteen years earlier was ending.

While Lynott was in the final stages of his life, addicted, depressed and struggling to create notable work with his post–Thin Lizzy band Grand Slam, he cowrote, produced and sang on this stately folk ballad. Something of an obscurity, it’s a collaboration with Clann Éadair, a group of fisherman who played traditional music in the pubs near Lynott’s Dublin home.

From Cowboy Song: Lynott added words to Clann Éadair’s tune, and somehow managed to turn a eulogy for a late folk singer into a lament for his own malaise: “I’m heartbroken, torn down / Oh Sandy, is there more to life than this? / Oh Sandy, I reminisce..” When the single was released he hustled the band a spot on [Irish TV program] The Late Late Show and appeared with them to sing it, dressed like a bad parody of a rock star but singing from the heart.

Cowboy Song officially pubs May 1, 2017 and is available wherever books and e-books are sold.

Cowboy Song officially pubs May 1, 2017 and is available wherever books and e-books are sold.

1 Comment

[…] recently wrote a blog for CRP on my favourite Lynott […]