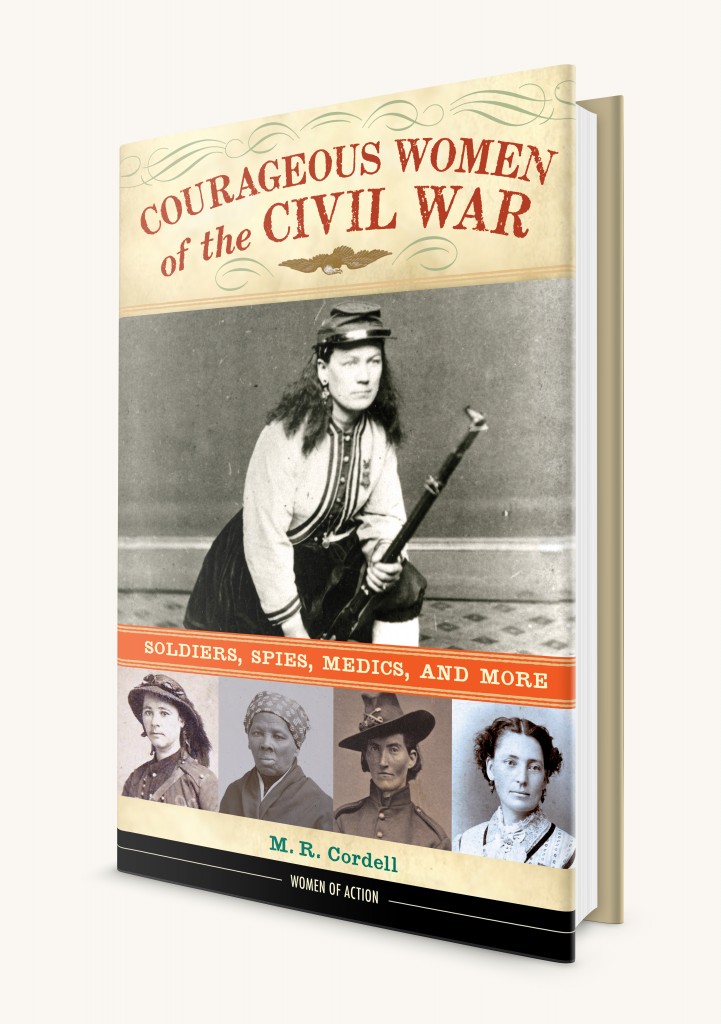

M. R. Cordell’s Courageous Women of the Civil War: Soliders, Spies, Medics, and More, the most recent addition to our Women of Action series, has been called “An excellent addition to history collections” by School Library Journal, “a solid resource” by Kirkus and “a rousing account” by Booklist. We sat down with Cordell to find out how she decided to write about these brave women and why their actions are relevant to today’s teens.

M. R. Cordell’s Courageous Women of the Civil War: Soliders, Spies, Medics, and More, the most recent addition to our Women of Action series, has been called “An excellent addition to history collections” by School Library Journal, “a solid resource” by Kirkus and “a rousing account” by Booklist. We sat down with Cordell to find out how she decided to write about these brave women and why their actions are relevant to today’s teens.

How were you introduced to women of the Civil War era? Was there one particular woman who piqued your interest and made you think of writing a book?

I read They Fought Like Demons, which is a carefully researched scholarly work about the women soldiers of the Civil War, and I was amazed by these stories of women who joined the army. Some followed loved ones into the service—fathers, brothers, sweethearts, or husbands. Some went because they could make good money as soldiers, a much better salary than they could earn as laundresses or domestics. And some simply wanted to fight for their country. Frances Quinn (who is better known as Frances Hook) was one of the women who dressed as a man to join the army. In a letter to President Abraham Lincoln, she wrote, “I am true blue and for [my] Noble Flag I am willing to die.” These women soldiers introduced me to the stories of nurses, spies, and vivandières [laundresses or cooks] who worked on and off the battlefield. That these women stepped outside their bounds was a big thing. If you think mansplaining is nuts, think about what women had to put up with back in the 1860s, when they were not allowed to vote or own property, when higher education was not encouraged. For a woman to take what was traditionally a man’s job was scandalous.

You write about both black and white women, and women from the North and South. What did you notice about how women were treated?

There is a heartbreaking similarity among the end stories for all the African American women. Harriet Jacobs worked in the South with homesteading black folks, but unscrupulous whites kept stealing their land away, burning their schools, and terrorizing them while the law looked the other way. Susie King Taylor’s son was sick—her husband had died, and he was all the family she had left. He lived in Shreveport, Louisiana, but she hoped to take him to Boston. The train refused to sell her a sleeping berth for him, so instead he died in Louisiana. Mary Richards tried to teach school in the South, but the law would not protect the schools or the people in them—schools were burned, and nobody was punished for it. Mary apparently left for the West Indies. After Maria Lewis’s spectacular work with the 8th New York Cavalry burning the Shenandoah Valley, a white man hit her in the face and bruised her eye considerably. Her only crime was being a black woman walking down the street.

Even the great Harriet Tubman was manhandled. After the war, as she was returning by train to her New York home, a conductor told her to move to the baggage car because, as he put it, “We don’t carry n*****s at half fare.” Harriet showed her army pass, but the conductor hauled her out of her seat. When she resisted, he called on three more men to throw her into the baggage car, breaking her arm and possibly her ribs and wrenching her shoulder. She could not work because of her injuries; the railroad would not pay her medical bills. She had to burn her fences that winter because she had no money for firewood.

Of the 16 women you profile in the book, do you have a favorite?

I can’t really choose a favorite, but I do like that I have a local Missouri gal in the book. Early on in my online research, I learned about Mary Carroll. She’s from Pilot Grove, Missouri, about three hours from my home. Mary’s brother and his friend were thrown in the Cooper County Jail, accused of aiding in an attempt to kill a Union man and his family. They were sentenced to be executed before a firing squad. Mary and one of her friends blistered their hands making an iron key that would unlock her brother’s cell and set him free. Mary’s account, The Secret of the Key and Crowbar, had a lot of good details that I really wanted to include in my book. My first draft of Mary’s story was about 8,000 words. I had to whittle it down to 2,000!

How did you start your research? Were there any particularly helpful or surprising  resources you came across?

resources you came across?

A great number of publications from the 1860s—books, newspapers, service records, regimental histories—have been digitized and are available and searchable online. For many women, I started my research by going directly to their principal researchers. Maria Lewis escaped from slavery and passed as a white man, and she rode with the 8th New York Cavalry. Dr. Anita Henderson had been researching Lewis for decades after finding her mentioned in a Quaker woman’s diary. As I followed up on Dr. Henderson’s research, I went off in some directions of my own and found diary entries that provided Maria’s full story and her male alias.

How are women’s actions during the Civil War relevant to young adults today?

Human nature never changes. This is why we can read books and enjoy stories that are thousands of years old; this is why history always repeats itself, but also why we can learn from the past. Young women today are just as brave, bold, and smart as these Civil War women—and they have more opportunities, too.

Courageous Women of the Civil War by M.R. Cordell officially pubbed August 1, 2016, and is available wherever books and e-books are sold.

“Cordell gives a rousing account of 16 women who defied traditional roles to serve as soldiers, spies, medics, and vivandières during the American Civil War.” —Booklist

“An excellent addition to history collections.” —School Library Journal

“The biographies include photos of some of the women and provide a fascinating and engaging look at their activities, motivations, trials, and later lives. Excellent, detailed backmatter adds to the volume’s usefulness. A solid resource.” —Kirkus Reviews

[Get it now $20] [Request a review copy]

No Comments

No comments yet.