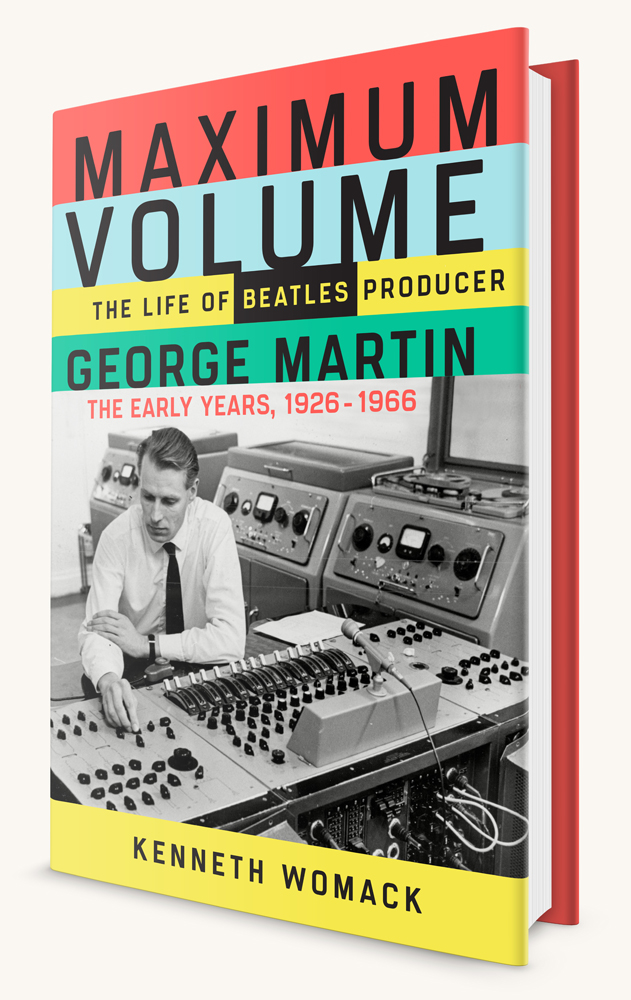

Kenneth Womack is a Beatles scholar and the author of Maximum Volume: The Life of Beatles Producer George Martin, The Early Years, 1926–1966. Womack delivers some 50 invited Beatles talks a year to audiences across the country and shares his insights with media of all stripes, including NPR, ABC, NBC, CBS and Voice of America. Here Womack discusses the research process for the first full-length biography of Sir George Martin, the term “maximum volume” and, of course, tells us about a few of his favorite Beatles songs.

I have to start with this question: What are your top three favorite Beatles songs?

Trying to choose your favorite Beatles song is a difficult task in and of itself. Our rosters of favorite songs tend to change over time, and mine is no different. Lately, I’ve been thinking about my favorite Beatles songs as milestone moments. In that spirit, “I’ll Be Back” is an important early composition for me. As the closer for A Hard Day’s Night, “I’ll Be Back” was the first song to conclude a Beatles album on anything less than a robust, rock ’n’ roll note, which afforded it with greater poignancy and impact.

If I had to choose a single Beatles song that encapsulates their creative achievement, it would be “A Day in the Life,” the finale of Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band. Hands down, it makes for their most luminous accomplishment, a genuine work of art that Martin and the Beatles slaved over to get exactly right. Nothing marks a great artist like being self-conscious about their work, and the Beatles recognized—and were in awe of—the experience and importance of recording “A Day in the Life.” In a similar fashion, Abbey Road’s “The End” finds the Beatles self-consciously concluding their career on a self-conscious note of optimism and goodwill—not to mention, sublime musicianship from all four bandmates.

What was the research process like for this book? As a Beatles scholar, were you already familiar with George Martin’s life story?

I was definitely familiar with Sir George’s life and times before embarking upon the work associated with Maximum Volume. But the research process for this project was challenging, given the enormous amount of published material related to his biographical life—and in particular his association with the Beatles. Of special concern was the issue of his existing autobiographies. They’re incredible resources, but at the same time, they are the product of their author’s sometimes faulty memory. Hence, the challenge of composing Maximum Volume involved sifting through mounds of extant material and attempting to ascertain the accuracy of the available scholarship within the context of the new information that I have gleaned through interviews and other primary materials. This had led me to believe that, in many ways, George was the unreliable narrator of his own life. I mean no disrespect by the comment; I believe that this aspect of telling oneself would be true for just about anyone. But it also means that we have to be ever vigilant in terms of trying to establish which stories are the most accurate and for which the most evidence is available.

George Martin seems to have had an eclectic taste in music. He started out as a jazz scratch pianist, and all of the Beatles albums he worked on have very different sounds. What were some of George’s musical influences?

One of George’s earliest influences was Debussy. And when you listen to a composition such as “The Girl with the Flaxen Hair,” you can hear the sound of his own compositional practices, and in some ways the sound of the Beatles, in its staves. Interestingly, in his 1995 appearance on the BBC’s Desert Island Discs, George’s eclecticism was on full display. His favorite tracks ranged from Ravel’s Daphnis and Chloe and the Beatles’ “I Want to Hold Your Hand” to selections from Beyond the Fringe and Mozart’s Oboe Quartet in F Major, among others. The sense of variety in those offerings is very telling indeed. But taking the notion of a “desert island disc” to its logical conclusion—with these songs being the ones that would ostensibly afford you with cultural sustenance until your rescue—George’s list is pretty strange. I say this because his selections invariably involve tracks that he produced. It makes me wonder: would he enjoy listening to his own work and contemplating the different choices that he might have made in their production? Or would he be better off choosing tracks that weren’t associated with his career—tracks that might better send his heart soaring in his most desperate, loneliest time of need?

The Beatles said when they first met George, they thought he was pretty posh even though George actually had a working-class childhood. He also seemed to have a great sense of humor whenever he interacted with the band. Do you think that’s part of the reason he got along so well with the four boys from Liverpool?

George and the Beatles definitely shared a strong reverence for humor and its key place in human interaction and connection. But the fact that he seemed so very posh to them, if only initially, was very important in establishing the course of their relationship. At 36 years old, George seemed like the oldest man in the world to them when they first met him. Throw in the accent and his background as a navy veteran and you can see how intimidating he might have seemed to them in class-conscious England. Having said that, the working-class heritage that they shared may very well have been the most important aspect of their working relationship: both George and the bandmates were motivated by and valued a strong work ethic. That sense of purpose is evident on nearly every one of their musical collaborations.

In one part of the book, you touch on how George Martin and the Beatles wanted their records to have a bigger and bolder sound, just like the American imports that they loved. George said, “Getting maximum volume out of those grooves became my major preoccupation.” Could you explain how this “maximum volume” led to the band’s success?

I am particularly taken with George’s concept of “maximum volume” as a play on words. On the one hand, he was referring to the notion that he wanted to produce Beatles records that absolutely blew listeners away, that possessed an inherent loudness to them. He wanted a Beatles sound that would drive fans right from their transistor radios into the record shops. “You, the listener, would hear it over the radio for the first time,” he exclaimed, “and it would knock your socks off. Out you would go to the record store and buy it. That’s the business.” It was the business, in short, of creating maximum volume. But on the other hand, he also wanted to produce maximum volume in the form of one release after another. Like Brian Epstein, he saw this self-conscious market domination effort as a way to consolidate the Beatles’ fame. Back in those days, more than one critic tried to categorize the Beatles as a “flash in the pan,” and Martin and Epstein were determined to thwart that characterization at every turn. And a whole truckload of new Beatles product seemed like the best way to combat those kinds of assertions.

Kirkus Reviews called the book “An authoritative account of pop-music history and the man who helped shape it.” He always seemed to be ahead of the curve. Would you say that George Martin was ahead of his time?

Actually, I would take a different tack in responding to this question and suggest that George wasn’t necessarily ahead of his time; rather, he recognized his time when it came. To my mind, that is the essence of genius, which is a word that we bandy about way too often. George’s genius came in realizing that the Beatles were his life’s work. And as the book points out in great detail, he was rather late in coming to that realization. But when he finally came around after the Beatles recast “Please Please Me” with a faster tempo at his suggestion, he never looked back. He threw in his lot with those four young men—they were kids, really—out of the North Country. It must have seemed absurd to him at the time—even as he was doing it—but he simply couldn’t stop himself after the fateful events of November 1962. He had glimpsed something special in them, and he was determined not to look away.

As a fan of the Beatles, were you surprised by anything you learned about George Martin or the Beatles?

There are very few revelations at this point that surprise me. But every time I take a deep dive with the Beatles, I am astounded by the sheer improbability of their achievement, much less their enduring success. With all of the factors at work—namely, that they came out of Liverpool, that the world expected very little from them—they simply shouldn’t have happened. In many ways, it is about like studying the demise of the Titanic. With those newfangled watertight compartments and the latest technology, the liner should very well have steamed unscathed into New York Harbor in April 1912. So many things had to go wrong for the ship to founder, and those things came about in spades. For the Beatles, so many things had to fall their way—and virtually every one of them did. But second only to their discovery by Brian Epstein in the Cavern’s dank basement, their meeting with Martin was the absolute making of them. He was the one person who, should he choose to take them on, had the capacity to see them through the incredible creative shifts of which they were capable. But who else could have glimpsed it but George, who had remade himself from his humble origins into a bona fide gentleman, and made good on it?

What do you hope Beatles fans take away from Maximum Volume?

One of my favorite aspects of George Martin and the Beatles’ story concerns the ways in which they came together as relative outsiders to the record industry. The Beatles were the ultimate outsiders, of course, hailing from Liverpool. As Ringo always used to say, “We’re rednecks from the sticks.” That is an essential truth about their place in Great Britain’s class-oriented society. And then you have Brian Epstein, who also found his origins in Liverpool—and also happened to be homosexual in a time when it was criminalized. And he was Jewish, to boot. These were challenging aspects in a culture where difference wasn’t tolerated in the same ways we celebrate diversity in the present day. Like the Beatles, he had no inroads into the British music industry. And then you have George Martin, who grew up on the wrong side of the tracks only to remake himself, even going so far as to fashion a new accent. When it came to working at EMI, he was a novice in terms of production and engineering. But together, Martin, Epstein, and the Beatles succeeded in disrupting an entire industry, shaking it to its foundations, and remaking it on their own terms. It’s really quite stunning to imagine that those six men could will themselves into a force to be reckoned with and upset a multinational business. It boggles the mind, on one hand, while reminding us that a few people really do possess the power to change the world.

Bonus: Non-Beatles recordings produced by George Martin

Shirley Bassey, “Goldfinger”

Cilla Black, “Anyone Who Had a Heart”

Peter Sellers, “A Hard Day’s Night”

Peter Ustinov, “Mock Mozart”

“An authoritative account of pop-music history and the man who helped shape it.”—Kirkus

“Maximum Volume is not only an excellent book and brilliant read, but it needs to exist. ” —Spill Magazine

“They seemed an unlikely partnership—the Beatles, who knew everything about rock and roll music, and their classically trained producer George Martin, who knew very little. But as Kenneth Womack uncovers in this engrossing and forensically detailed biography, the recording studio became a ‘magic workshop’

and George Martin a musical wizard when it came to the Beatles’ songs. A fascinating read.” —Ray Connolly, author of Being Elvis

Maximum Volume hit the shelves September 1, and is available wherever books and e-books are sold.

[Order it now $30] [Request a review copy]

No Comments

No comments yet.