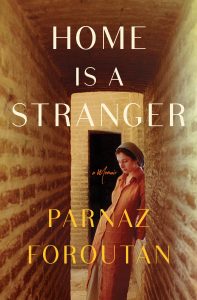

Home Is a Stranger is the new nonfiction travel title from the break-out novelist and recipient of a PEN Emerging Voice fellowship Parnaz Foroutan. Her memoir is about the meaning of desire, the transcendence of boundaries, and the journey to find home.

With this being the first time Parnaz took on the nonfiction genre, we wanted to know her thoughts on the differences between writing fiction and nonfiction and if she had a preference for one or the other.

I’m going to tell you a story. Once upon a time, we sat in the comfort of our living rooms and one evening, the headlines read that in market in a city in China, a few merchants were sick. We read that story, and moved on. A few nights later, the headlines told us that authorities had closed that market, that the merchants were in critical condition, and doctors were scrambling to understand why. We read that story and moved on. The headlines screamed that a silent killer, a stealthy one, moved through that city. We read, we paused, we moved on. The city was shut down, the people shuttered in their homes. We read. We waited and watched, pensively. It was in Japan, now. It was in South Korea, now. On boats in the middle of the sea, in mosques, on airplanes, it moved with speed and before we knew it, it was here. Now.

I don’t think there is much distinction between writing fiction and nonfiction. Narrative is narrative. As writers, we tell a story. And all stories, regardless, are born of the stuff of the imagination. I’ve always preferred the photograph to the painting, it is a personal aesthetic choice, the photograph is closer to reality as I understand it, and for me, the function I want art to serve is to show me reality through a different lens. So when it comes to writing, I prefer stories that are grounded in actual events, stories of real people and real places. My first book was a work of literary fiction, but it was a retelling of the oral history of my family, several generations back. I was given the bones of that story as a child, when I would sit at the Shabbat table and listen to the elders speak. Two decades later, I sat down at my writing desk, and took the bones of that story, and told my own. How do you define that genre? It is a true story, in that it happened, the facts of it, sort of… Perhaps?

I did a lot of research to write that first book. I read a lot of history books, with titles like The Study of Muhammadan Magic and Folklore in Iran. The main character of my book, the protagonist of the elders’ Shabbat stories, she used to carry a heavy ring of keys with her wherever she went. I read in this history book that women in early 19th-century Iran carried keys as a sort of talisman against evil spirits. I was thrilled by this discovered fact; I ran to my grandmother and told her, “Rakhel carried those keys to ward off evil spirits!” And she told me, “Those keys were to the locks of the storeroom where the food was kept. Those keys gave Rakhel a lot of power within the household.” How do you negotiate those two facts? Who do you grant authority to—my grandmother, or the Orientalist who studied Muhammadan magic? Which narrative is fiction, and which is the other?

I don’t know if when we sit down at our desks to write, if we ought to give much thought to genre, really. When we sit down at our desks, and we are about to engage in the act of writing, the greater task is clarity, and honesty, and the responsibility to create something pure and good and true. Fiction, or non.

No Comments

No comments yet.