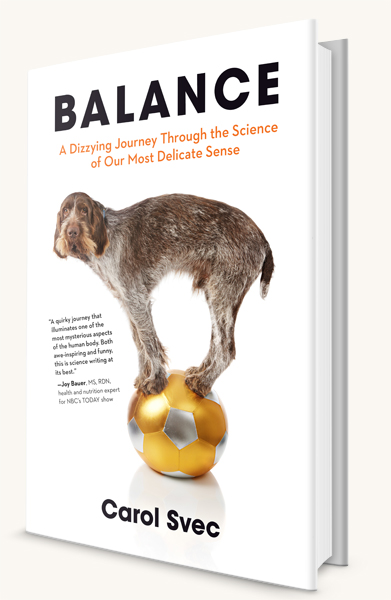

Balance: A Dizzying Journey Through the Science of Our Most Delicate Sense by health and wellness writer Carol Svec examines every facet of our most complex and fragile sense. Throughout Balance, Carol visits university labs to experience the latest research devices that are applied to help those who are ill, elderly, disabled or are simply prone to queasiness and motion-sickness. Balance also reveals what potentially life-changing advances may be on the horizon.

Balance: A Dizzying Journey Through the Science of Our Most Delicate Sense by health and wellness writer Carol Svec examines every facet of our most complex and fragile sense. Throughout Balance, Carol visits university labs to experience the latest research devices that are applied to help those who are ill, elderly, disabled or are simply prone to queasiness and motion-sickness. Balance also reveals what potentially life-changing advances may be on the horizon.

This week is Balance Awareness Week (September 18–24), so we thought we’d ask Carol some questions about what inspired her to write Balance, what she learned from visiting labs across the country and how she developed her unique writing voice.

What inspired you to write this book? Were you already well-versed on the subject of balance?

A few years ago, I helplessly watched as my mother lost her balance on some stairs. She fell straight back, knocking her head on the concrete garage floor. She’s fine today, but her injuries were serious—skull fractured in two places and three areas of brain hemorrhage. During her recovery, balance was the last thing to come back. It took months before she could walk without assistance, and years before she felt steady on stairs and escalators.*

That was the first time I recognized balance as a physiologic entity, with its own capacity for damage and its own timetable for recovery. Before my mom’s fall I never gave balance much thought. It certainly wasn’t part of any of the physiology classes I took. I realize this sounds naïve, but when I thought of balance, I remembered being a child trying to maintain balance while walking on the edge of a curb. I thought balance happened when there was proper alignment of legs and body. While researching this book, I quickly learned that all parts of our bodies are involved in maintaining balance, and that leg muscles are just a small part of a complex system.

[* I am my mother’s eldest daughter, and we have always been very close. That first night in the emergency department was tense and terrifying . . . but it also started a continuing family joke. Head injury patients are given recognition tests to determine their level of awareness. My mom was asked if she knew where she was (in a hospital), if she knew what brought her to the hospital (she didn’t remember the fall), and if she knew her name (she did). At that point I leaned over to let my mom have a good look at my face, and asked if she knew who I was. She drew back, glared at me and said, “No! Why the heck would I?” Trust me: My sisters have fun reminding me how forgettable I am.]

Closer view of the optokinetic drum.

Balance is filled with hilarious first-person accounts from you of what it’s like to be a scientific guinea pig. At one point, you sit in an optokinetic drum, otherwise known as “the Vominator.” What made you want you want to try out these experiments yourself?

Who wouldn’t jump at the chance to experience something called “The Vominator”? I think it was the same instinctive pull that makes us buy tickets to go on the most outrageous ride at a carnival. (My personal favorite was a behemoth called the Octopus. It had long metal “arms” with spinning cars at their ends, while the arms rotated around a center hub and also moved up and down.) Science writing mainly involves computer research and paperwork. The Vominator and other legitimate scientific devices were fun and instructional, and they got me out of my office. How could I resist?

Joy Bauer, health and nutrition expert for NBC’s TODAY show called the book “A quirky journey that illuminates one of the most mysterious aspects of the human body.” Why do you think balance is so mysterious to us?

We are used to having our body senses neatly partitioned—eyes control vision, ears control hearing, the tongue controls taste, and so on. Balance doesn’t fit into that encapsulated mold. Instead, balance is woven into the very matrix of our being. Every part of the human body contributes in some way to the seemingly simple task of standing still without falling. That same system can adapt to more complex balance demands—dancing, skiing, gymnastics. All those activities are possibilities within each of us because of our sense of balance. All that power, energy, and coordination is completely integrated throughout our bodies. It is simultaneously everywhere, but nowhere. That’s the very definition of mysterious.

Your writing is quite similar to Mary Roach’s in that you make scientific research accessible and entertaining to everyone. How did you develop your (hilarious) writing style?

Any comparison to Mary Roach is a compliment and an honor. She is the master of entertaining scientific books that go where few other writers would dare. She is one of my writing heroes.

That said, when I’m writing, I never read other nonfiction books so I don’t unintentionally mix their writerly voices with my own. For many years, I coauthored health books with some amazing professionals who had the knowledge but needed help putting their ideas on paper. As a coauthor (or ghostwriter), it was my job to think and sound like the main author—I have to learn someone else’s voice, their pattern and tone of speaking.

When writing Balance, I had to rediscover my own voice. Some early chapters were rewritten several times because my friends and family would say the writing didn’t sound like me. I had to stop thinking like a generic scientist and allow more of myself on the page. When I finally let go and ran on my own, my voice emerged.

I think the humor in the book comes from being willing to embarrass myself, which—if we’re honest—is almost always funny when it happens to someone else. Friends (who say they love me) have told me that I have no “filter.” I say what I’m thinking before I weigh whether a comment is wise or not. Yes, it sometimes gets me into trouble, but mostly people laugh because I say the unexpected. I think I lost my filter after too many years spent locked in an office with a computer, a printer, and very little human interaction. I talk to myself when I write, so a filter became unnecessary. My writing voice is that raggedy part of me that grew in isolation.

What would you say was the most difficult part of writing Balance?

Early in my book writing career, when I felt overwhelmed by the sheer volume of information needed, a fellow writer told me about the old adage: How do you eat an elephant? One bite at a time. Concentrate on writing one paragraph, and then the next, and then the next. Before you know it, the paragraphs turn into pages, and the pages become a book. Organizing scientific material has not been a problem since.

However, in order to get the level of experience and detail I needed to write this book, I had to talk to and visit experts. I consider myself a relatively outgoing person, but cold-calling researchers I had come to revere was intimidating. Who was I, a lowly writer, to ask for an hour of time with internationally known experts? As I quickly learned, balance researchers are a lovely, warm, and highly enthusiastic bunch. Most spoke with me for an hour, many allowed me multiple phone calls, several offered to let me visit, and one—Dr. Laurence Harris of York University in Toronto—gave me an entire day touring and playing in his labs.

What’s the most surprising thing you learned from writing this book? Which experiment was your favorite to take part in?

Because I knew so little about balance when I began writing, there were a lot of surprises. But what boggled my mind was the concept of proprioception, our ability to sense the location of our body parts, as communicated by nerve fibers. If you close your eyes, you still know where your hands, arms, and legs are. It feels intuitive. And yet, it took a remarkable decades-long friendship and collaboration between a doctor and his patient to reveal nuances that could never have been known otherwise. The patient, Ian Waterman, lost his sense of proprioception after a viral illness. When he closes his eyes, he cannot sense where his limbs are. In fact, with eyes closed, he can’t even feel that his limbs exist. So how does a person stand steady and keep from falling if they can’t feel the location of his legs? Ian Waterman’s case provided answers, and a little-known side of the complex balance network.

Hans in the Tumbling Room. Note all the details.

My absolute favorite bit of apparatus was the Tumbling Room. Imagine sitting in you favorite chair in your living room and suddenly feeling yourself begin to spin sideways, like the chair is doing cartwheels. That was the feeling I had in the Tumbling Room. But in reality, the room was spinning; my chair and I were stationary. Because everything in the meticulously decorated room was glued down (including a surfer-dude mannequin named Hans), there were no clues that it was moving. We expect an upside-down room to follow the laws of gravity, but not a single hair on Hans’s head moved. That gave a powerful illusion that I was the one doing the spinning. It was exhilarating, and I laughed all the way through the demonstration from surprise and delight. The Tumbling Room reminds us that a simple trick of the mind can fool our sense of balance into believing we are upside-down and moving, even though our chairs are bolted to the floor.

What do you hope readers take away from Balance?

I hope readers discover that balance is mysterious and wondrous in a world woefully short on wonder. We are only beginning to piece together its complex connections. This overlooked and highly sensitive sense is always “on.” Each second, our brains process and translate thousands of balance signals from all over the body with the dedicated goal of helping us stay steady on our feet. Balance is among the last physiologic frontiers. How cool is that?

“Thoroughly informative and engaging, Svec’s “dizzying journey” maps a crucial, too-little understood aspect of health and well-being.” —Booklist

“Thoroughly informative and engaging, Svec’s “dizzying journey” maps a crucial, too-little understood aspect of health and well-being.” —Booklist

“With crisp, lucid, and witty prose, Svec leads us on a kind of Odyssean journey into the secret symphony performed every second of every day between our eyes, ears, brains, nerves, joints, and even blood. Who knew ‘balance research’ could tell us so much about ourselves? I didn’t, and was bowled over by the whole thing. This is less a book about the misunderstood sense of balance and more a paean to the clever clockwork of the human body.” —James Nestor, author of DEEP: Freediving, Renegade Science, and What the Ocean Tells Us about Ourselves

“Never again will I understand the mere act of standing upright as anything less than a small miracle. Carol Svec’s exploration of balance is unexpected, engaging, and ultimately enlightening.” —Samantha Dunn, author of Not by Accident: Reconstructing a Careless Life

Balance: A Dizzying Journey Through the Science of Our Most Delicate Sense was published on September 1, and is available wherever books and e-books are sold.

No Comments

No comments yet.