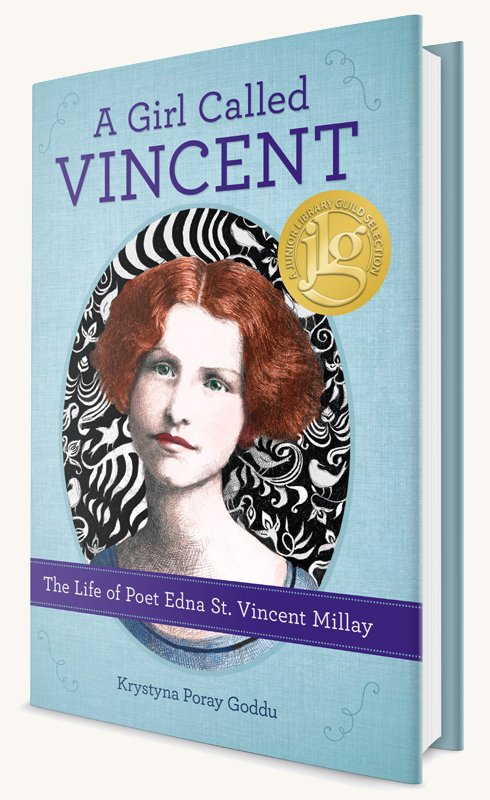

We’re excited to publish Krystyna Poray Goddu’s A Girl Called Vincent: The Life of Poet Edna St. Vincent Millay during National Poetry Month 2016. This is the first biography of the Pulitzer Prize-winning poet Millay, who went by Vincent, published for middle-grade readers since 1969. Here Goddu reveals her love for Vincent’s poetry and why it was important for her to share Vincent’s life story with a young audience.

We’re excited to publish Krystyna Poray Goddu’s A Girl Called Vincent: The Life of Poet Edna St. Vincent Millay during National Poetry Month 2016. This is the first biography of the Pulitzer Prize-winning poet Millay, who went by Vincent, published for middle-grade readers since 1969. Here Goddu reveals her love for Vincent’s poetry and why it was important for her to share Vincent’s life story with a young audience.

Many people are familiar with Edna St. Vincent Millay’s line “My candle burns at both ends,” from her poem “First Fig,” which appeared in the June 1918 issue of Poetry Magazine. My first encounter with Vincent was in fifth grade, when I read Anastasia Has the Answers by Lois Lowry—Anastasia memorizes “God’s World” for English class. How were you introduced to Vincent?

I found her poem “Renascence” in a poetry book I was reading one night when I was about 12 years old. I don’t remember what the collection was, but I do remember that when I started reading the poem I thought it was very simple, and that I could write better than that. It probably reminded me of a poem I had written a few years earlier with the same meter; mine began “I sit beneath a shady tree/I’m all alone, I’m being me.” But as I kept reading I was mesmerized by what happened to the speaker. I was completely taken in by the experience and the words she used to express it. It seemed to me the epitome of a profound spiritual experience, and it moved me very much. And I struggled for years to understand the closing couplet.

Vincent had quite an unusual childhood in Maine—looking after her two younger sisters alone while her mother worked as a nurse away from home for days and weeks at a time. Did you know about this part of her life before starting your research for the book? Did you relate to her in any way?

Vincent had quite an unusual childhood in Maine—looking after her two younger sisters alone while her mother worked as a nurse away from home for days and weeks at a time. Did you know about this part of her life before starting your research for the book? Did you relate to her in any way?

I did know a lot about her unusual childhood before starting my own research, and I thought it gave her story strong appeal for children. And, no, I did not relate to her or her childhood in any way except in writing from an early age, which I did. My childhood was the exact opposite of Vincent’s; I grew up in a highly structured three-generational family with extremely strict European parents and grandparents. My brother and sister and I were never left alone for any period of time! I have often thought that if Vincent met me as a child (or adult, probably), she wouldn’t have the time of day for me! I was a very well-behaved child.

Why were you compelled to share Vincent’s life story with this age group? Did you run into any issues portraying her adult life as a “rock star” poet?

I love reading and writing for the middle-grade audience because I feel these readers are still open to inspiration and not yet jaded. They are looking to be moved and empowered by books as well as to glean all the information they can from them. I’ve heard it said that writers write for the age that they remember best from their own lives, so I think that must be part of it. I still love to read middle-grade stories in which the protagonist, after some identity struggle, begins to “discover” herself or himself.

And yes, because I was so familiar with Vincent’s life story before I began writing, I knew there would be many challenges as I delved into her early adulthood. In fact, when I told people I was writing about Vincent for a young audience, those who knew about her were sometimes shocked and disbelieving that it could be done at all. She was a very sexual being; she was unashamedly bisexual. She had a teasing, often sharp, tongue and could also be cruel and hurt people. Then in her later life, as she became more and more addicted to alcohol and then to drugs, she became quite a sad figure. I knew I’d have to address all these things, but not dwell on them, and present them in language that was not explicit. But I also believe strongly that many children today encounter these issues in the lives of those around them—sometimes in the lives of those very close to them—and I wanted to tell a story that showed these issues as part of a life that was filled with extraordinary accomplishments. I am especially proud that some of the reviewers of the book pointed out this aspect as well-handled.

Tell us how you went about researching Vincent’s life. What did you learn that surprised you? Were there any resources that were particularly valuable?

Doing the primary research was one of the most exciting endeavors of my life! I had been reading anything I could find about her for years, and I especially relied on Nancy Milford’s Savage Beauty and Daniel Mark Epstein’s What Lips My Lips Have Kissed, both published in 2001, when working on my proposal. Many decades ago I had found a used copy of the 1952 Letters of Edna St. Vincent Millay, so I was familiar with her “non-poetry” voice. So I can’t say anything I learned really surprised me. What did surprise me was the vast amount of primary source material at the Library of Congress. The Millay family was so prolific in their diary-keeping and letter-writing, and saved EVERYTHING. Pressed flowers fell out of envelopes postmarked 1913, for example.

I made several trips to the special collections at the Vassar College Library, where library specialist Dean Rogers introduced me to the protocol of working with original materials in that setting. It was at Vassar that I first held a piece of paper with Vincent’s handwriting on it. I was nearly shaking with excitement. Then I made a number of trips to the Manuscript Room at the Library of Congress, where much of the Millay material is held. It was my first time at the Library of Congress, and I was blown away by what a public treasure it is. Pretty much anybody can come in and request material that is of interest, for personal or professional purposes. And there I encountered Vincent’s first diary, a simple brown notebook with “1907” written on the front cover. When I held that in my hands and opened to the first page to read, in her handwriting, the words I had already read in other books, I literally had tears in my eyes. And of course, I visited Steepletop, her home in Austerlitz, NY, that is open to the public, numerous times. It’s a beautiful spot and well worth a visit.

Did you have any unexpected experiences while researching?

A fun story about serendipity—the day after I handed in my manuscript, I had lunch with a new friend. She began telling me about her grandfather, who had been a well-known writer in his day, and how she had gone to Chicago to the Newberry Library not long ago to do some research on him. The Newberry Library rang a bell with me; I had recently learned about it when I was trying to find out who held the rights to material by Vincent’s first male lover, Floyd Dell. I knew a lot of his writings were there. Suddenly I remembered the name of my new friend: Jerri Dell. Slowly I asked, “What was your grandfather’s name?” When she replied, “Floyd Dell,” I believe my mouth literally fell open. She was shocked. “How do you know Floyd Dell? Nobody’s heard of Floyd Dell anymore!” I told her about the manuscript I had just delivered, and then her mouth fell open. We sat in the restaurant quoting lines of Vincent’s poetry at each other. The fact that this all took place in a Ruby Tuesday in a remote part of western Maryland made it especially astonishing to both of us. Needless to say, a warm friendship has developed between us!

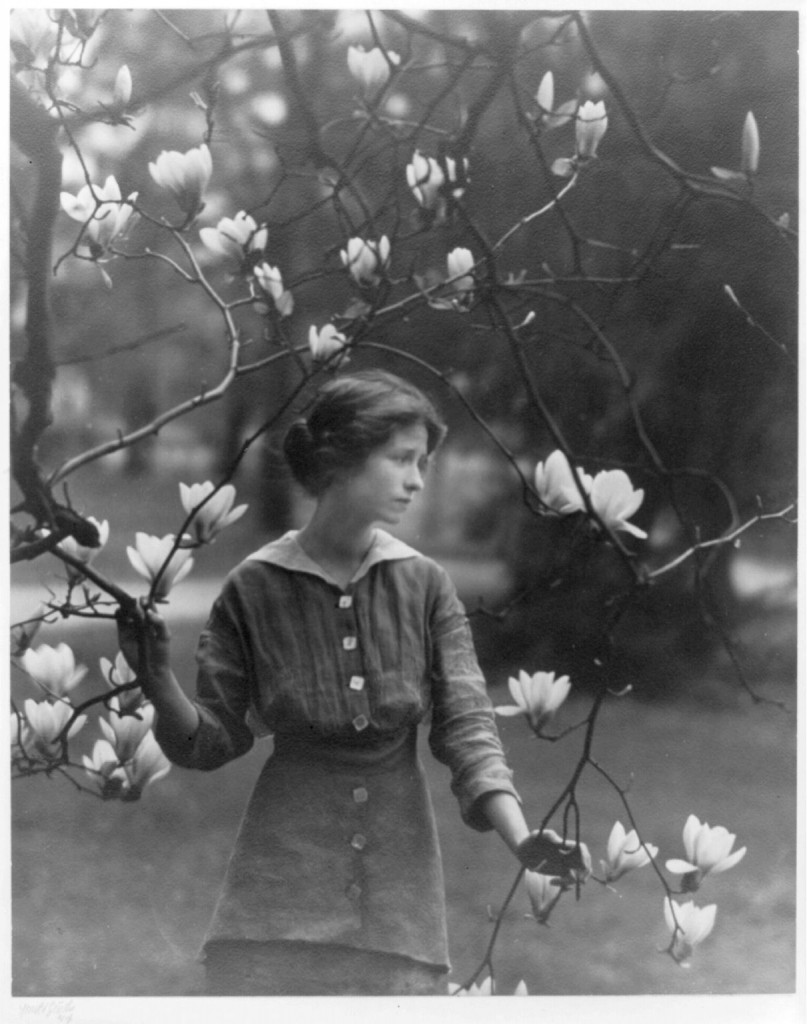

The most famous photo of Vincent, taken by Arnold Genthe. Mamaroneck, New York, 1914. Library of Congress

There hasn’t been a biography of Vincent published for this age group since 1969. Why do you think this is? What do you hope young readers take away from your book, Vincent’s life, and her poetry?

Sadly, interest in Vincent and her poetry largely fell away over the decades after her death. Fashion in poetry had changed dramatically (which was already happening during her lifetime, of course, but her public personality overrode that, I believe, and kept people keenly interested in her poems) and “serious” critics and writers dismissed her as one of those lady poets who wrote in classical forms. When we were trying to sell this book, editors (except for Lisa [Reardon], of course!) would say “Oh, I love her work but nobody reads her anymore.” One of my goals in publishing this book is to change that. I’m so grateful to Lisa for her excitement about sharing Vincent’s life and poetry with young readers.

Also, until the Library of Congress acquired her papers in the late 1990s, it was very difficult to access the primary source materials. So people were just rewriting the same anecdotes—often not even true ones—over and over in books.

I hope readers take away several things from my book: an appreciation for the extraordinary passion with which Vincent led her life and wrote her poetry and an understanding of how pioneering she was to live as she chose, uninhibited by social mores, and to write poetry that expressed a woman’s rawest emotions—in the most exquisite classical forms. She was never an activist in the suffragette movement,  but her life was emblematic of feminism in an era when women had barely won the right to vote. I hope they are inspired by Vincent’s spirit and aware that life lived with that kind of passion and rebellion also holds dangers.

but her life was emblematic of feminism in an era when women had barely won the right to vote. I hope they are inspired by Vincent’s spirit and aware that life lived with that kind of passion and rebellion also holds dangers.

And of course, we’re wondering: What’s your favorite Millay poem and why?

Such a tough question! So many favorites…the love sonnets, most of all, with lines like “What lips my lips have kissed, and where, and why, /I have forgotten” and “Pity me that the heart is slow to learn/What the swift mind beholds at every turn.”

But going way back, when I was reading Millay before any romantic heartbreaks entered my life, I think my favorite has always been the one I quote at the end of Chapter 4, “Travel.” The third and fourth lines—“Yet there isn’t a train goes by all day/But I hear its whistle shrieking” always comes to mind whenever I hear a train whistle. I think what I love most about that poem is that the speaker is happy with her life: “My heart is warm with the friends I make…” and yet that train whistle is so full of promise—of adventure, of other lives to be lived. It speaks to the allure of possibilities. It made me want to travel when I was a young girl, and then when I did travel, in later adolescence and early adulthood, I would think about that poem and how both Vincent and I did take that train, so to speak.

Goddu photo credit: Dave Romero/vibrantimage.com

A Girl Called Vincent is available wherever books (and e-books) are sold.

[Get it now $19] [Request a review copy]

Praise:

“While Goddu clearly likes her subject, she doesn’t avoid Millay’s rough edges, her bouts of depression or adult struggles with drug and alcohol abuse. However, parents need not be concerned. Goddu presents an honest portrait, appropriately tempered for a young audience.” —Down East: The Magazine of Maine

“To see Vincent through Goddu’s eyes is to see a most extraordinary story—one that, like Millay, belongs in any nonfiction collection.” —Booklist, STARRED

“[A] great option to recommend to aspiring poets, writers, and feminists, as well as those who enjoy historical nonfiction. A strong addition to any collection, especially those seeking out new titles for Women’s History Month.” —School Library Journal

“Goddu’s well-researched account produces an illuminating snapshot of the uphill battle female writers faced trying to earn a living in the first half of the 20th century. A revealing glimpse of a gifted poet whose impassioned works and acts are sure to capture the imaginations of young readers.” —Kirkus Reviews

“An obvious labor of love, Goddu’s biography of irrepressible poet Edna St. Vincent Millay (1892–1950) strikes a fine balance between academic presentation and devoted characterization of a life well lived.” —Publishers Weekly

No Comments

No comments yet.