Throughout Black History Month, we’ve rounded up weekly collections of Chicago Review Press books that explore the history of African American culture through various themes—social justice, kids, and music. We wanted our last post of the month to look forward, to add on to these collections of black history by looking through the lens of the future.

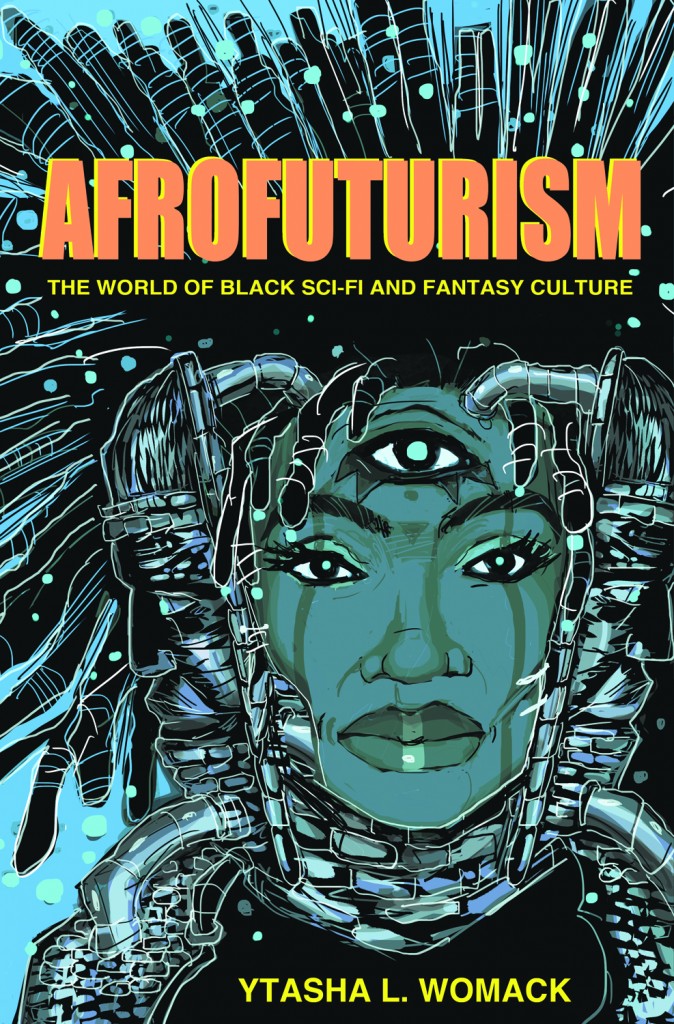

In her book Afrofuturism, author Ytasha Womack describes Afrofuturism as examining and redefining blackness through the “intersection of imagination, technology, the future, and liberation.” Read below for an enlightening interview with Ytasha on the past, present and future of African American culture.

What’s a category of Afrofuturism that has exploded in recent years that you could now easily write an entire extra chapter about?

I could write a chapter on the flurry of programs in Afrofuturism for teens that have sprouted up. The programs are looking to use Afrofuturism as a centrifuge to explore community development and creativity. I participated in one program with the University of Chicago called South Side Speculations in which teens created an art exhibit of inventions they thought could help their neighborhoods. The inventions ranged from augmented reality glasses that could locate community services to magical masks that could protect youth from police violence. I also think it’s fascinating to see how Afrofuturism inspires people who aren’t of African heritage around the world. Many people gravitate toward the subject because of the relative optimism and the intersections between art, science and history. They like exploring how the theories in Afrofuturism can contribute to building a future that values humanity.

What changes are you most excited to witness in the realm of Afrofuturism within the next five years?

I’m really fascinated with how students in high schools and colleges are connecting with the theories in Afrofuturism and how it’s inspiring them to think differently about the world. It will be interesting to see how Afrofuturism is used for real-world problem solving. We’ll also see more literature, art and comic books reflecting the ideas in Afrofuturism.

The theme of this year’s Black History Month is migration. How do you believe black migrations in the US influenced the black community, shaped its current culture, as well as the future?

Thinking about black migrations reminds me that I’m part of a continuum that was always in motion. In my travels around talking about Afrofuturism I’ve become increasingly aware that I’m a descendent of the people who moved to Chicago from Mississippi and Texas during opposing timelines in the Great Migration. I am very urban. I grew up in Chicago. I’ve spent a lot of time in New York, Atlanta and DC. This experience is different than say, if I grew up in Portland or Biloxi, MS. I grew up in ways where I could be in majority black environments and ethnically diverse environments. I’ve been in most neighborhoods around my own city which is something to say and clearly shapes my worldview.

My great grandmother on my mom’s side moved to Chicago from Mississippi for opportunity and to escape southern segregation. In that sense, I grew up in a city populated by people creating a future in Chicago that they couldn’t create in the areas where they grew up. I am living in what could have been the future of Mississippi. During enslavement, I had family in Mississippi and prior to that they were enslaved in Georgia, not too far from my college, and others were enslaved in the Carolinas. A DNA test connects my African ancestry to the Amazigh who are mostly in Morocco, Tunisia and Mali. Some came directly to the United States from Africa; others came through Central America. My dad moved to Chicago from Texas because he was inspired by activism. Before his family was in Texas, they were in Oklahoma and some lived on Native American reservations after the Civil War. My awareness of these migrations informs me, grounds me and connects me with a future.

As a teenager, I thought all young black people lived in big cities. I had very little understanding of teen life in the suburbs, middle America or the South. Attending Clark Atlanta University, an HBCU, for undergrad was great for me because I met teens from all corners of the United States and beyond whose experiences were clearly shaped by their regional experiences. I met kids who grew up near the Rocky Mountains, in rural towns, middle America, military brats, in addition to those larger cities and around the world. We enjoyed this exchange of regionalized culture. I think it’s significant to note that my grounding around ideas in Afrofuturism was shaped in Atlanta, a city with a large black population of people seeking a cultural utopia. My early experiences with Afrofuturism in Chicago dance scenes, house music as a norm, and metaphysics were experiences cultivated by people looking to create new futures. The unique black cultures in Chicago and Atlanta are a mix of the aspirations and the diversity of the black populations who moved there. People don’t always think about the diverse range of experiences in Black American culture and how that shapes the cultural output. Chicago and Atlanta have significant Afrofuturism scenes because of this mix of diverse migrants, aspirations, and a quest to redefine oneself beyond the boxes they are placed in. However, black people live in communities all over America and the stories around how they arrived there and the safe spaces they created are important. I do think it’s important to note that migrations continue. People continue to move to new places for safety and opportunity. They continue to seek community or in some cases to escape it. With gentrification becoming a greater issue, many are forced out of places they love and must build elsewhere.

My friends range in their migration patterns. Some are first or second generation descendants of Caribbean, Latin American or African immigrants. Some grew up in suburbs and moved to the city, others left large cities and moved to mid-sized towns in the South and new ways of life. Others left one large city for another and then moved back home to help with family. Others moved to Europe indefinitely. But in these migrations people are trying to create lives where they can feel good about themselves and create a life that falls somewhere in the realms of their dream life.

Mobility and exposure shape experience and in many ways can shape one’s experience as a person of African descent. Afrofuturism can be a bridge to explore these culture immersions.

What is the greatest difference you’ve noticed in how different generations experience African American culture?

I always like to note that at any given point in time you have multiple generations coexisting. So, the changing of the times, new technologies, new opportunities can impact all these generations at once. So, the prevalence of Facebook or climate change impacts you whether you’re in high school or a retiree. The same can be said for social justice movements. The intersection of the freedoms facilitated through social justice, media and technology can enhance or impede an African American person’s agency and their ability to be self-sufficient, across generations. You also have highly progressive people in each generation. A Baby Boomer could have had ideas for technologies that a millennial had but due to lack of access to capital or the prejudice of the times weren’t able to act on it.

The greatest difference is really shaped by reference points, new opportunities and traumas that defined coming of age moments for each generation. I wrote a chapter on this in my book Post Black: How a New Generation is Redefining African American Identity. I could write an entire book on this subject. However, the greatest difference that stands out to me is each generation’s relationship to community.

Baby Boomers coming of age lived in physical communities with a bevy of organizations and religious entities that gave them identity and immersed them in African American culture. Even if they broke away from a community, they could reintegrate into another one and still had relationships with the old one. They were likely to experience African American culture in a group dynamic by default. Gen Xers lived in times when these institutions were going through radical transformations or were disintegrating, and urban areas were dealing with the impact of drugs and underinvestment, but they still had physical experiences with community and African American culture. Millennials came of age when this idea of community was increasingly online, school affiliated or part of an affinity group. As a result, some African Americans’ relationships to black culture today is more digital than it is physical or it’s a unique combination of both. Millennials are more likely to discover their favorite song on a streaming service than to hear it at a club with a group of people and a deejay. Many people must go out of their way to create group experiences to know black culture. This was prevalent with Gen Xers whose parents moved into mostly white suburbs and would bring them into cities to be part of a family organization. Gen Xers parents in the North would send city kids to the South for the summer to know family and southern culture. However, as gentrification in urban cities continues people will have to actively create collective experiences in the absence of their being an automatic neighborhood or black cultural group that they are a part of.

Also, I think that generations today have a greater ability to opt out of African American culture if they choose. They can move to a town or hang around people who aren’t black and choose never to engage with anything affiliated with the culture. Anywhere they go they are African American but that doesn’t mean they know black culture or have any family or societal ties that will foster a relationship with it. It also doesn’t mean they value it. And knowing African American culture is more than listing the popular rap songs of the day and one’s experience with discrimination. Most Baby Boomers coming of age didn’t have that opt out option.

Last week’s blog post for Black History Month contained a collection of biographies of black musicians. In terms of Afrofuturist music, what musician(s) have you come across recently who you see as pushing those boundaries of cultural norms?

I’m a big Childish Gambino and Janelle Monae fan. Childish Gambino might be more surrealist or Afrosurrealist in some ways than Afrofuturist but I think his mix of music of different times and layers in both the LP “Awaken, My Love” and the song “This Is America” are bridges through time. Janelle Monae creates inspiring music that explores identity, archAndroid narratives, and empowered women in the future. I really lean toward the experimental and rhythmic. I really like live beat music. I like King Britt. He curated Moondance at the MoMA PSI and his Fholston Paradigm albums are stellar. I really like his LP “Black Unicorns.” I’m looking forward to hearing the soundscape he did with the augmented reality mural in West Philly. Nicole Mitchell is a creative flutist and composer from Chicago originally and her work is inspired. I like her song “Mandorla Awakening.” Angel Bat Dawid is a composer clarinetist from Chicago and her new LP “The Oracle” is all magic. I like Sons of Kemet. Kamathi Washington and Flying Lotus are amazing. I also like Moor Mother and her radical explorations of sound and phrasing. She really pushes boundaries. Ras G is a favorite of mine, too. The Philly rapper Sammus makes fun, fresh music. I’m still replaying Beyonce’s Lemonade. For anyone looking for a survey of Afrofuturist sounds, check out the Spotify Afrofuturist playlist I cocurated with Janelle Monae called Black to the Future.

No Comments

No comments yet.