A Promise Kept: Editing Rainbow Warrior

by Jay Blotcher

When a friend dies suddenly, the ritual of mourning is upstaged by pragmatic concerns: notifying the family, hunting for a will, making funeral arrangements, and cleaning out the apartment.

When my friend Gilbert Baker unexpectedly died in March 2017, these were all urgent considerations. But there was another pressing issue: preserving Gilbert’s legacy. For Gilbert was the creator of the Rainbow Flag—the global symbol of LGBTQ+ liberation.

Gilbert in self-designed garb as Miss Liberty. San Francisco, 1980. Photo by Mick Hicks

Since he sewed the first Rainbow Flag in 1978, Gilbert had been at the forefront of seminal moments in LGBTQ+ liberation: Fighting the notorious Briggs Initiative. Protesting after the assassination of San Francisco supervisor Harvey Milk. Protesting again when Milk’s killer received the slightest of convictions. Working with Cleve Jones to create the NAMES Project AIDS Memorial Quilt. And so much more.

As a freedom fighter, Gilbert sewed and stitched his way through several revolutions, creating scores of protest banners and Rainbow Flags (two long enough to be named in the Guinness Book of World Records), all on his own sewing machine. Small wonder why he was known as the gay Betsy Ross.

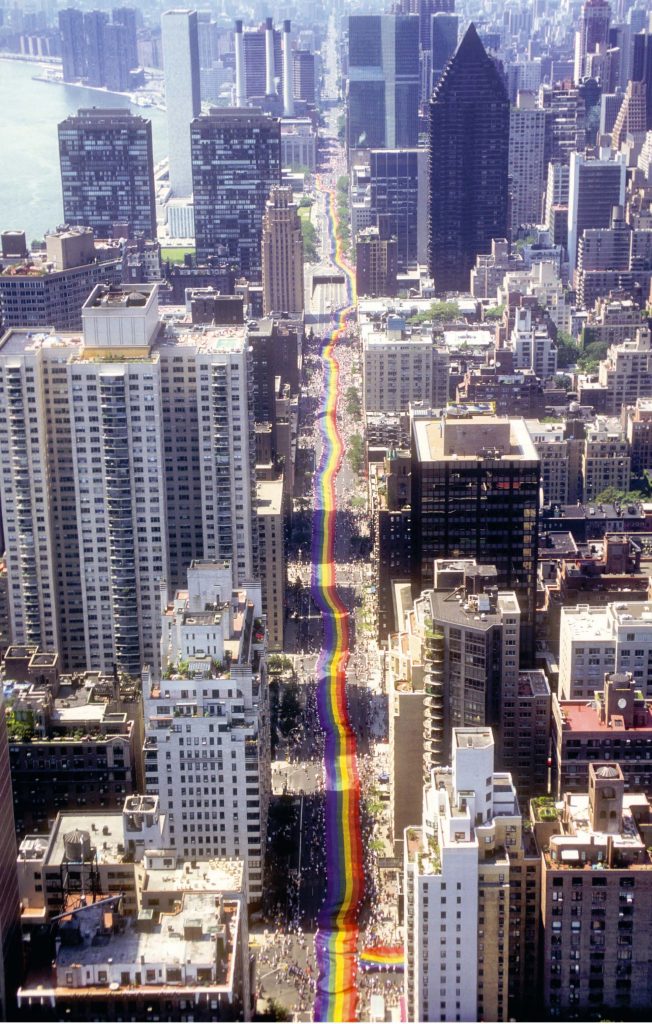

Thousands of volunteers worked in unison to carry Gilbert’s mile-long flag along First Avenue during Stonewall 25 on June 26, 1994. Photo by Mick Hicks.

Gilbert knew the score: history is written by the victors. America’s tradition of homophobia had guaranteed that LGBTQ+ people were virtually removed from the annals of history. In defiance, Gilbert decided to write his own memoirs. He started in 1996, working several years on the mammoth task.

Gilbert shared his first draft with me back in 1997, dumping a heavy sheaf of white pages into my hands with a fragile look of expectation. A journalist by trade, I had been helping several friends edit their manuscripts—including Michelangelo Signorile’s 1993 Random House classic Queer in America.

Gilbert made me promise to edit his book.

As we planned his memorial service, Gilbert’s memoir was uppermost in our minds. Charley Beal, Gilbert’s dear friend and activist ally for a quarter century, created the Gilbert Baker Estate. This foundation would ensure that future generations know of Gilbert’s achievements. The estate made his artwork and flags available to museums and galleries. It also focused on making the memoir a reality. Charley received the blessing of Gilbert’s mother and sister to move forward.

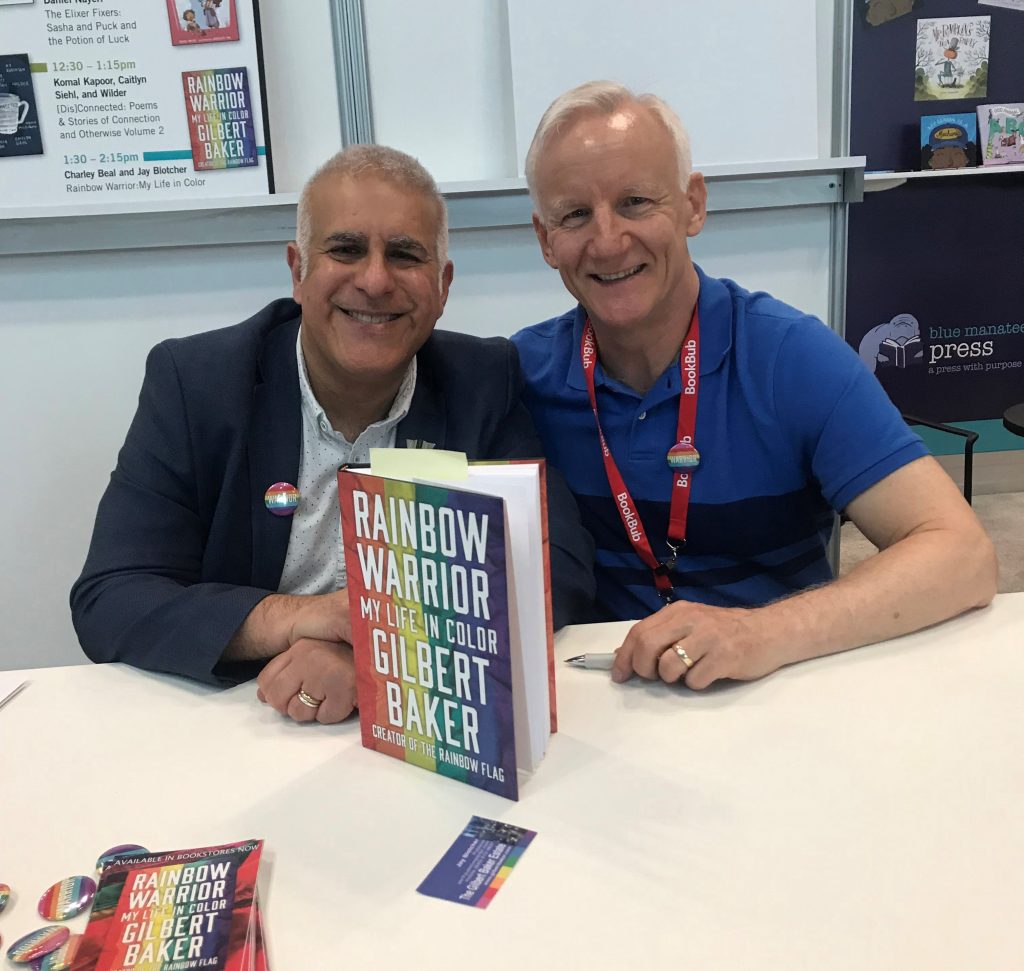

Jay Blotcher (on the left) and Charley Beal (on the right) representing Gilbert Baker’s memoir Rainbow Warrior at BookExpo. Photo by Michael Huber / NYS Writers Institute, University at Albany.

Gilbert’s lifelong friend Cleve Jones—who had published his own memoir, When We Rise: My Life in the Movement—connected Charley with his own literary agent, Robert Guinsler, a powerhouse at the august agency Sterling Lord Literistic. Guinsler recognized the power of Gilbert’s life story and stepped in to represent the property. In an industry in which people work years to find a literary agent, this was a boon to the project.

But first Charley had to evaluate the state of the manuscript. Gilbert had given him several drafts over the years. Charley had offered encouragement along the way, and sympathies when Gilbert was initially rebuffed by publishers. Disappointed but not thwarted, Gilbert returned to the material, rewriting extensively. However, the exigencies of activism, as well as the siren call of art, distracted Gilbert frequently from his writing project, as did a 2012 stroke that required months of rehabilitation.

Gilbert was not a professional writer, but he was a born storyteller. Moreover, his talents as a visual artist informed his writing, bringing a vivid imagery to his prose. And as he toiled away on rewrite after rewrite, Gilbert evolved into a stronger author.

But the real revelation was to come when Charley gained access to his late friend’s computer.

Gilbert presents a hand-dyed Rainbow Flag to President Obama at the White House’s 2016 LGBT pride Month reception. Photo courtesy of the Barack Obama Presidential Library.

Here, the literary project suddenly morphed into an archaeology project. Buried on Gilbert’s hard drive were a groundswell of rewrites, orphaned chapters, and other addenda. Charley found numerous stray chapters, sometimes in mislabeled files.

At this point, I was officially brought on board. As a friend of Gilbert, it was impossibly bittersweet that I was now editing the memoir but without my friend here to work with me.

Being a manuscript editor is an intense collaboration. You serve as the author’s copy editor, confidant, life coach, and therapist—insisting that every painful cut, every disfiguring deletion, is done to strengthen the work.

In this case, I did not have the author over my shoulder, protesting my edits. Nor did I have him to ask questions, request clarification, or to challenge the occasional grandiose scenario. (Gilbert was a diva, after all.) Happily, I was able to quiz Charley and other friends for factual authentication.

Editing the text of “My Life as Betsy Ross” (Gilbert’s original title) was a career highlight—and the challenge of a lifetime. With each excavated rewrite, the master draft became a more mammoth saga, running past 400 double-spaced pages. I wanted to do justice to Gilbert’s momentous story. But I also wanted to produce a book of manageable length, something not to be left gathering dust on shelves.

Robert Guinsler at Sterling Lord approved my first draft with modest edits. Then I worked with Chicago Review Press editor Jerry Pohlen and copy desk magician Devon Freeny on additional edits. Over the course of 18 months, I invested 300-plus hours into transforming a boisterous, passionate, vibrant, and lengthy story into an epic memoir that rightfully will take its place in American history.

Just as I had promised Gilbert 22 years ago.

Gilbert, as Busty Ross, crowned “Most Political” drag queen at the 2012 Invasion of the Pines on Fire Island. Photo by Charley Beal.

Jay Blotcher is a veteran book editor (for hire), a publicist with Public Impact Media Consultants, and a journalist whose work appears in 12 anthologies.

Order Rainbow Warrior: My Life in Color by Gilbert Baker here.

2 Comments

Beautiful tribute to your friend Jay!!!

Jay, your superb writing skills are surpassed only by your deep commitment to your friends and your sense of obligation to do what’s right. Your masterful work on Gilbert’s book is now a part of history, and rightfully so.