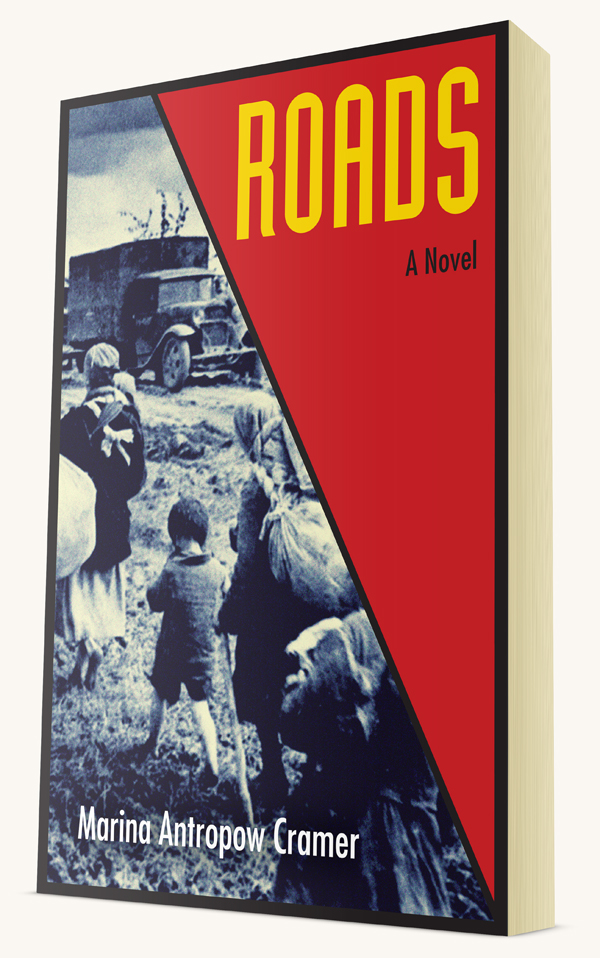

In Marina Antropow Cramer’s debut novel, Roads, a family of Russian refugees must find new meanings for loyalty, fidelity, grief and love among the chaos of World War II.

In Marina Antropow Cramer’s debut novel, Roads, a family of Russian refugees must find new meanings for loyalty, fidelity, grief and love among the chaos of World War II.

Filip and Galina grew up side by side in the sun-drenched beauty of Yalta, but what’s left of their youthful romance will have to carry them into more turbulent times. Though a hurried marriage should helps them avoid Germany’s forced labor camps, they cannot evade that fate for long. Soon the newlyweds, along with Galina’s aging parents, cling together during the brutal physical toil and constant hunger. After Dresden burns to the ground and the family barely escape with their lives, they are quickly torn apart by the war, Galina left to fend for herself with her mother and newborn child. Looking for safety in an alien land, they move towards a reunion through the help of refugee networks and pure chance.

Marina talked with us about life as a bookseller turned novelist and about writing family lore into fiction.

You had a splendid book tour in New York and New Jersey in May and June. How have local bookstores and libraries supported you as a debut novelist?

Is it splendid? As a debut novelist, I have no frame of reference. But as a bookseller, I know how unpredictable author events can be. It’s been heartening to experience the level of interest and attention people have expressed, whether in small groups or larger gatherings. I’m looking forward to meeting with book groups as the tour continues, to hear their reactions after they’ve read the book.

In an interview with Shelf Awareness, you talk about how being around books nourished you. What was your favorite part of being an indie bookstore owner and bookseller? How did it influence your writing?

I loved all of it! Ordering, unpacking, shelving, arranging, display. Spending many hours every week surrounded by books, and wondering, once Roads began to take shape, if and how it might fit among them.

Most of all, I was fed by the conversations—with colleagues who were constantly reading (it’s a job requirement, and a necessary passion), and with customers, staying open to preferences other than my own, like as not. It helped me look at things from different sides, to examine motivation, see various points of view, each in its own way legitimate. I think having these book discussions as part of my daily bookselling life helped me find a way to represent the characters’ differing views. Or so I hope.

You traveled to several different countries to conduct research for the book. Where did you go, and how did focusing on research affect your experience?

I didn’t go to examine documents or track down family connections, the way one would if doing scholarly research. I was looking for general impressions, landscape, language, the kind of history that’s written on people’s faces, the ways they relate to each other and to strangers. Part of my Europe trip was nostalgic—I had lived in Brussels as a child, and was curious to see how it had changed. (A lot.) I also went to Germany, saw Dresden and Regensburg and their famous rivers, the Elbe and the Danube. I enjoyed the food, the beer, the vibe.

The Russia trip was like a homecoming in many ways, a revelation in others. Coming from an expatriate family, I hadn’t lived under Communism, didn’t share that history with people who were otherwise culturally close to me. And I didn’t get to visit Yalta, where much of the story is rooted. I don’t know if that’s a good thing or not, whether the Yalta of my imagination gives a true picture of this very real place. I’d heard about it all my life, so maybe not seeing its modern aspect helped me draw a more accurate wartime version.

The Historical Novels Review said that in Roads, “Style derives not from emotionally-charged prose but from elegant syntax and precise word choice.” Do you have a favorite passage stylistically? Or perhaps one that took the most revision to become a favorite?

Hard to choose! There was so much revision along the way, all of it necessary if not immediately self-evident. Maybe this one, with its allusion to past events without explanation or comment:

“He told her everything. The wedding registry, the lucky green tie, the firewood, the mushrooms. The white shirt dripping with red paint. Matted blond hair falling over Borya’s lifeless face. The bare feet. The drone of SS threats like distant thunder, a storm from which there is no escape. Everything. Even the things he could not put into words.”

You spoke with the Montclair Times about how your family’s stories of World War II influenced Roads. How did their experiences as Russian refugees contribute to the book? Was it challenging to blend family lore with fiction?

I think family lore lends itself to fiction because of the inevitable pitfalls of memory. With the passing of time, things that had seemed clear become tinged with nostalgia, details get transposed or forgotten. There’s the possibility of having misinterpreted events experienced in one’s youth when looked at from a mature perspective, with the benefit of reflection, of seeing a larger picture. In telling the story of my fictional characters, context became ever more important, the need to blend historical events with personal narratives. The fiction writer’s toolbox holds many wonderful things. Interpretation. Logic. Imagination.

In your Reader’s Guide for book clubs, you ask about how the characters’ challenges as refugees compare with today’s ongoing crises. How do you think Roads contributes to our current dialogues regarding refugees as well as Russian politics?

Today’s refugees have it much worse. Postwar Europe, with considerable help from the United States, had the will to deal with the plight of displaced people by establishing an administrative framework with the ability to dispense aid and reset refugees’ lives in a positive direction. There was resentment of the strangers in their midst who had to be accommodated, but there was also the vast work of reconstruction. Many hands were needed to rebuild bombed cities, to get factories into production and agriculture back on track. The people who leave their homes now face an unprecedented degree of xenophobia; the camps and shelters seem to be understocked, overcrowded and haphazardly run, which only adds to the general sense of distress and hopelessness. These are new problems requiring new solutions, and a greater generosity of spirit than we have lately seen. Maybe Roads contributes something to the discussion, maybe not. It’s not for me to say.

Today’s refugees have it much worse. Postwar Europe, with considerable help from the United States, had the will to deal with the plight of displaced people by establishing an administrative framework with the ability to dispense aid and reset refugees’ lives in a positive direction. There was resentment of the strangers in their midst who had to be accommodated, but there was also the vast work of reconstruction. Many hands were needed to rebuild bombed cities, to get factories into production and agriculture back on track. The people who leave their homes now face an unprecedented degree of xenophobia; the camps and shelters seem to be understocked, overcrowded and haphazardly run, which only adds to the general sense of distress and hopelessness. These are new problems requiring new solutions, and a greater generosity of spirit than we have lately seen. Maybe Roads contributes something to the discussion, maybe not. It’s not for me to say.

As for Russian politics, with the steady slide back into repressive policies peppered with strategic opportunities for obscene wealth and privilege, who knows how that will end.

What do you hope readers take away from this novel?

Oh, pleasure in the reading of it, above all. Perhaps a recognition that our essential humanness knows no national boundaries, that we really can—and do—understand each other. And that the underlying mechanism, the thing that makes it all work, is love.

Roads is on sales now and is available wherever books and e-books are sold.

1 Comment

One of the best novels of historical fiction I’ve read, mainly because the author allowed the characters to be alive on the page, as real people speak and react. The book held me cover to cover.